In the year 2017, 128,000 people moved out of the capital (while 95,000 moved in). Most recently, 200,000 Parisians left their city during the confinement. But leaving Paris does not mean leaving the Paris region. (Olivier Léon, Insee).

Leaving Paris for the countryside, a city-dweller’s dream, is however not a statistical reality, or at least not yet. It is the reality of today’s job market. Leaving Paris does not mean leaving the Paris region: 55% of those leaving have stayed in the Paris region, the majority of them in the Paris metropolitan area. Half of the others are found in large provincial cities. Departures for the “countryside” are therefore in the minority, and often by retirees.

Working couples, with or without children, continue to work in Paris but move away from it for a larger home. The same trend is at work for the inhabitants of the Paris metropolitan area: whether they live in the region or on its outskirts, a large number of them work there. At the regional level, the arrivals of new workers are almost as numerous as the departures.

At the time of confinement, 200,000 inhabitants of Paris intramurals left their city for other departments. Did this exceptional exodus amplify a groundswell of departures from the capital? Census data do not say so (yet?).

To determine whether Parisians are leaving Paris, we must first agree on the territory we are talking about. What is generally understood by “Paris” or “Parisians”? Inhabitants of the capital (intramural Paris)? Those of the Parisian agglomeration, in the sense of urban unity? Or, more broadly, those of the “Paris region”, i.e. the Île-de-France region? We will see that in each of these areas, migrants have similar motivations.

Parisians who settle “in the country” are much less numerous than those who stay in the Parisian agglomeration

As far as the “inhabitants of the city of Paris” are concerned, taking into account only the flows with the rest of metropolitan France, nearly 128,000 of them left the capital in 2017 while about 95,000 people went the other way around.

Of those who left the capital, more than 71,000 stayed in the Île-de-France region, and even in the Paris metropolitan area for the majority of them. They are mostly young adults, who make “leaps and bounds” when they move. They settle close to Paris, looking for larger and more accessible housing, especially when they get together as a couple. More than 80% of them are active and nearly half work in Paris. For couples without children, mobility “outside Paris” has increased: they will account for 27% of departures in 2016, compared with 23% in 2008. These earlier departures, even before the arrival of the first child, are contributing to the demographic slowdown observed in the capital and the decline in births.

There are 57,000 people who have moved further afield in the province. Half of them move to large cities (Bordeaux, Lyon, Nantes) and the other half to less densely populated areas. Parisians who settle “in the country” are therefore much less numerous than those who stay in the Parisian agglomeration. Retirees are more represented among these “long-distance” residential migrations. The net migration of people aged 65 or over with the rest of France is traditionally in deficit (-4,100), but remains stable. Among these seniors, 60% choose to settle in the provinces, mainly in coastal regions. It should be noted that more than a quarter of the seniors who leave Paris settle in a special care facility for the elderly.

Conversely, those moving to Paris are younger. The 15-29 age group accounts for 63% of these arrivals. They come to study or take up their first job.

In 2017, 20% of people who have left the Paris metropolitan area will stay in Île-de-France

As regards residential mobility between the Paris metropolitan area and the rest of the metropolis, exchanges are also in deficit, as in Paris. In 2017, nearly 245,000 people left the conurbation, also known as the Paris urban unit, compared with 150,000 who joined it.

Attractive areas, even on the outskirts of Paris

Of those who left the Paris metropolitan area, nearly 20% stayed in the Paris Region. This local mobility contributes to peri-urbanization.

It is mainly families who settle in Yvelines, but also in Seine-et-Marne and Essonne. These last two departments even have migration balances with the rest of France close to zero, with arrivals and departures balancing each other out. On a more local scale, some areas of the Ile-de-France region are even attractive, with a positive migratory balance. They are located southwest or east of Paris.

Among the 200,000 or so people who settle in the provinces, many are moving “locally”, particularly to the neighboring departments of Eure-et-Loir, Oise, Loiret and Yonne. There are also 80,000 people who travel longer distances, particularly to the cities of Lyon, Bordeaux, Toulouse and Nantes.

In the opposite direction, two thirds of those arriving in the Paris area, mainly young adults, come from the provinces, particularly the metropolises of Lyon, Toulouse and Lille. The remaining third come from the rest of the Paris region, especially Yvelines, where nearly 10% of newcomers come from.

More than half of the people who left the Paris Region for another French region were not born in the Paris Region.

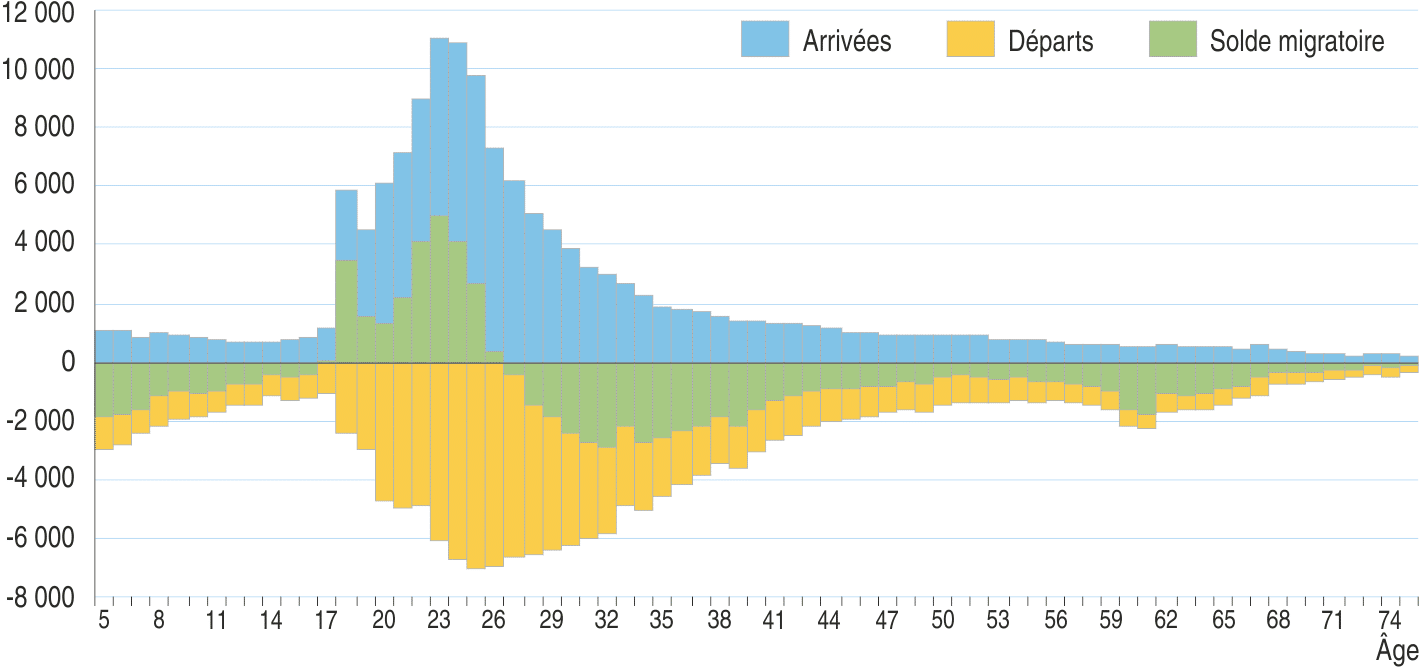

On the scale of Ile-de-France, again excluding international migration, there are 231,000 departures and 137,000 arrivals in 2017.

Of the 231,000 people who left the Paris Region for another French region, more than half were not born there. These are people who “leave” after having come to live in the Paris Region for a longer or shorter period of time to study or work. These departures most often concern families with child(ren). The other departures are older. Among couples without children, the reference person in the household is 40 years old or older in almost half of the cases (less than one out of four among new arrivals, excluding those moving abroad).

Indeed, among the 137,000 people who will have settled in Île-de-France in 2017 from another metropolitan region, almost two-thirds are young adults (62% are between 18 and 34 years old). Completing one’s studies explains the migration of 23,500 students aged 18 or over). However, the bulk of migrants have mainly come to work: 82,000 are employed. Many of these new Ile-de-France residents will return to the provinces after their studies or after their first work experience. Nearly three-quarters were not born in the region.

Arrivals and departures in Île-de-France

Source: INSEE, population census 2017

A migratory deficit with the rest of the French territory to be put into perspective for the Ile-de-France region

If we limit ourselves to only those who are employed, the Ile-de-France’s migration deficit with the rest of the country is divided by twelve and falls to 8,000. If we add those who have left the region while continuing to work (23,000) and we subtract those who have settled in Ile-de-France but do not work there (4,000), the balance is even positive in terms of employment for the region (+ 11,000). In fact, a quarter of employed workers who have left the Île-de-France for another region continue to work there. The majority of them have settled in one of the eight bordering departments. In some of these departments (Eure-et-Loir or Oise), nearly a quarter of employees work in Île-de-France. The movement of students (18 years or older) between the Paris Region and the rest of the country also leads to a positive balance for the region with 23,500 arrivals and 18,000 departures.

The balance of migration with the rest of France is only one of the three components that contribute to the variation of the population. When the natural balance is added, the populations of our three perimeters fall much less when they do not increase. In Paris, between 2012 and 2017, the population fell by about 11,000 people per year, with the natural balance offsetting the migration deficit with the rest of France. The urban unit is gaining 57,000 people per year, with the migration deficit vis-à-vis other metropolitan territories being more than offset by foreign arrivals and the natural surplus. As for the population of Ile-de-France, it continues to grow, by 55,000 per year, due to a natural balance, the highest in Europe.