At the invitation of the Crimhalt* association, the families of victims of the recent settling of scores in Marseille have just immersed themselves in the land of the Camorra. To learn from the Italians of the anti-mafia how to position themselves in the face of organized violence. We were there with them.

By Frédéric Crotta

Meeting the victims of the Mafia (1)

Exactly 30 years ago, on March 19 at precisely 7:20 a.m., shots rang out in the sacristy of the Basilica of St. Nicholas of Bari in Casal di Principe. On his feast day, Don Peppe Diana, who was preparing to celebrate mass, had been shot five times: twice in the head, once in the face, once in the hand and once in the neck. The assassination was the work of the local Camorra, against whom the priest had always fought with modest means.

Marseillaises and Corsicans

Since then, every year on the same date, a large number of the town’s 21,000 inhabitants have paid tribute to the priest. It begins with a mass at the time of the priest’s murder, followed by a march from the town center to the cemetery. The march included Marseillaises Atika, Laetitia, Jasmine, Hassna, Ouassila and two Corsicans, Jean Toussaint and David. They too were affected by the death of a loved one.

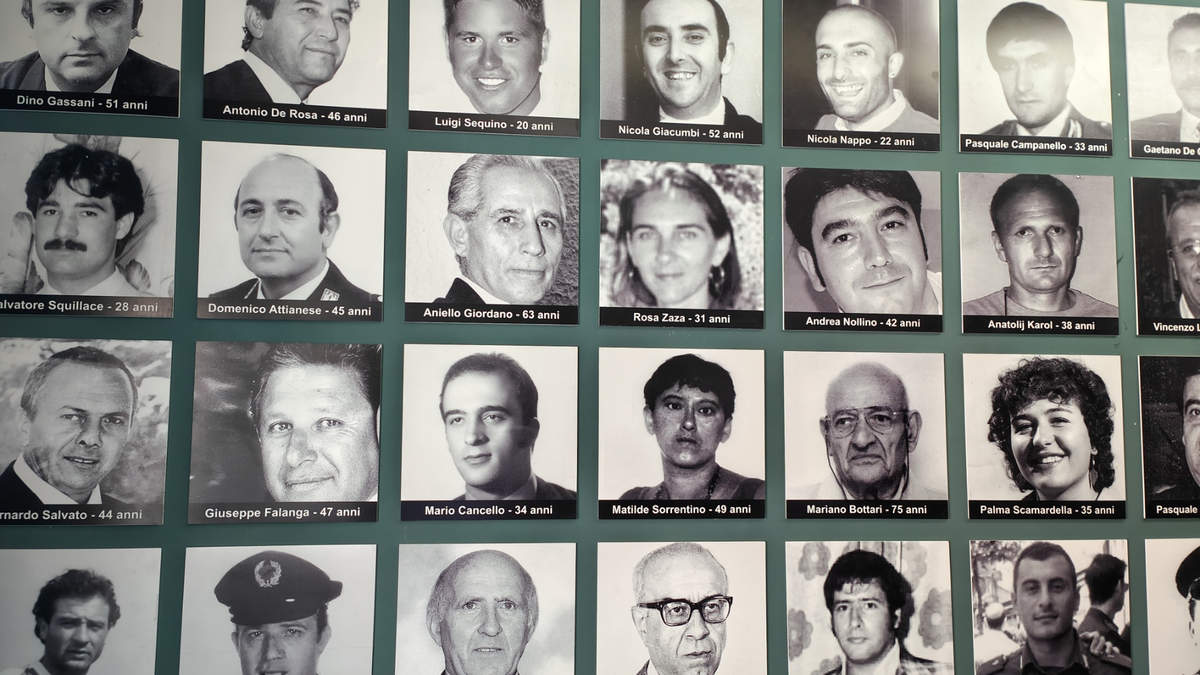

At the end of the parade, many locals take turns at the microphone, set up on a platform, to recite the names of the 1081 victims murdered to date by the Mafia in Italy. Casal di Principe is the stronghold of the Casalesi, one of the most important families of the Camorra. Racketeering and drug trafficking are the main activities of this Mafia organization, which operates in the Neapolitan region. Over the years, this octopus has spread its tentacles into all strata of society. Even if the number of recorded homicides has fallen somewhat in recent years.

The priest’s death was an electroshock, and his struggle has left its mark. Not only in Campania, but throughout Italy, he has become an icon of anti-mafia activists and a symbol of resistance to organized crime.

35,000 properties confiscated

In Casal di Principe, although still active, the Camorra has lost some of its power. Some fifty properties belonging to “bosses” or simple executors of the organization were seized and then confiscated. Some of these assets were made available to associations. From the 1980s onwards, the Italian justice system sequestered over 35,000 villas, apartments, properties, warehouses, hotels and businesses. In all cases, the idea is to redistribute these assets to associations working in the social economy. For example, at NCO, one of the restaurants seized and visited by the French group, service is provided by autistic adults.

“Orders to kill”

The Don Diana Committee, created in memory of the murdered priest, has set up shop in a magnificent 1,500-square-meter residence that once belonged to a killer. “In the past, orders to kill came from here,” explains Neapolitan academic Michele Mosca.

Today, this imposing building houses a cultural and memorial center. This “Casa don Diana” organizes workshops for schoolchildren. It is here that the families of French and Italian victims have been able to exchange and compare their respective experiences of “violent death” and the loss of a loved one. Interspersed with sobbing, the stories of brutal disappearances in both Marseille and Italy were told. Whether the victims are mafiosi or drug traffickers, most of the time whole families explode, smashed against the wall of incomprehension and violence. While in Italy, over the years, solidarity has been built up, as demonstrated by the powerful Libera movement, in France, everything remains to be done. Laetitia Linon, the aunt of a young man gunned down in Marseille, is enthusiastic and swears that once she’s back home, she’ll be running around the TV studios telling people what she’s seen here, and explaining “how the Italians deal with innocent victims and go after the thugs’ wallets.”

Next article: “When a Camorra boss’s house becomes… a police station” (2/3)