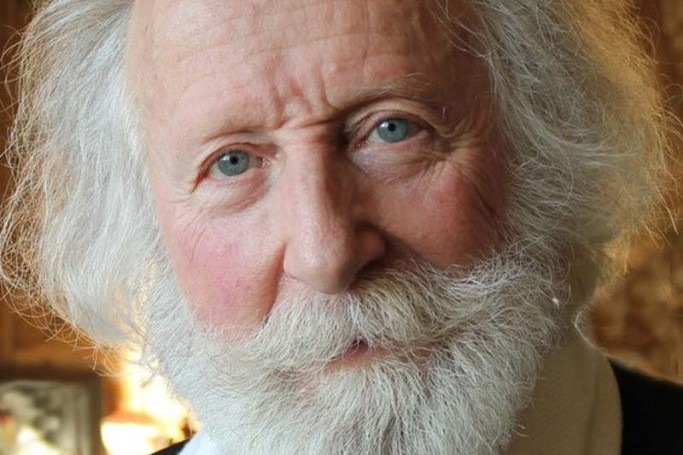

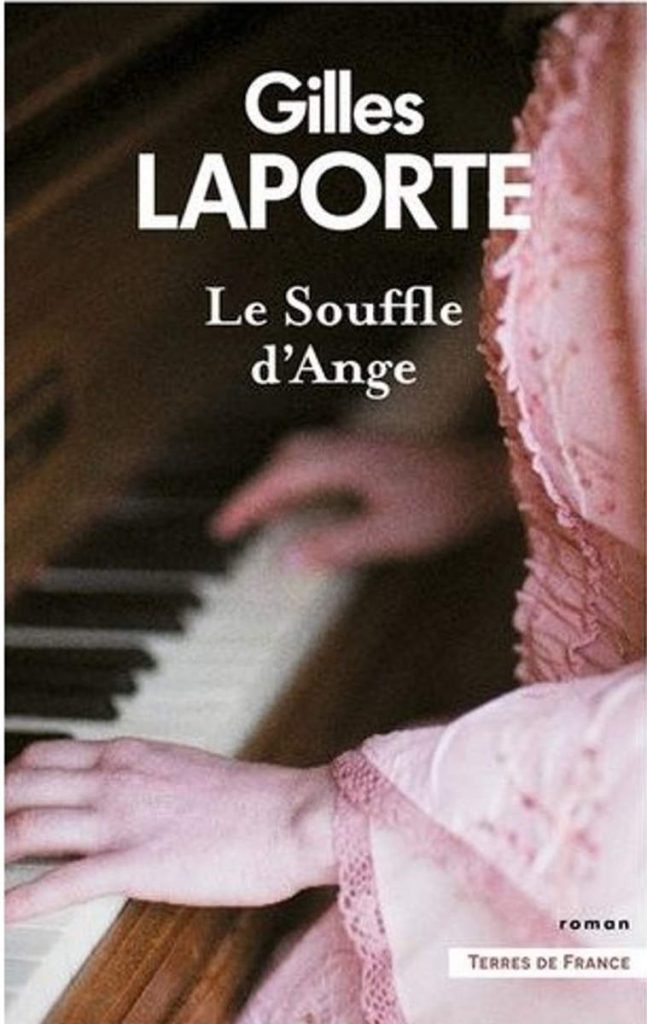

The Lorraine author will present his new novel “Le Souffle d’Ange” (ed. Presses de la Cité) at the 44ᵉ edition of the Livre sur la Place, September 9, 10 and 11, 2022 in Nancy. He tells us why and how he writes. Interview.

As always, Gilles Laporte’s novels are also history books. His characters are so interwoven with the reality of the settings and historical events that they take on flesh before our eyes. Such is the case with Ange, a young girl as beautiful as the day, who shares with us her passion for music to the point of becoming one of the great figures in organ building.

Ange discovered music one day in 1903, in the Abbey of Saint-Georges de Saint-Martin de Boscherville, in Normandy, with her parents. As they entered the great church, “a rich organ voice greeted them, rose up under the vaults and began to sing the amber notes of a nightingale, then to flow in rivers of harmonies, breaking in roaring waves. Ange is subjugated by this music which “addresses itself to the soul to unite it to God”. And by this magnificent instrument of which she admires the decorations of the case with foliage and fruits, the spandrels with fleur-de-lis, the gilding of its three turrets.

Normandy and Lorraine

Ange found her vocation. She decided to devote her life to organ restoration. Married to a young and handsome Italian, Fortunato, she goes to Lorraine, in the Vosges, to train at one of the most prestigious manufacturers of great organs of the 19ᵉ century, Jaquot-Jeanpierre.

When the Great War broke out, Fortunato went to the front. But he will come back from it diminished. Ange loves him with all her soul and helps him as best she can. She devotes herself with passion to her work, giving life to tired instruments.

A life of hard work and beautiful encounters: Jean Marais, Louis Majorelle, one of the great names of the Nancy School, Gaston Litaize, an organist from the Vosges.

And then again the war. In October 1944, Ange experienced another wonderful moment with the new approach of the Lesselier organ in Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville, in Seine-Maritime, his native Normandy. A return to her roots which reminds her of her first emotions when, for the first time, in 1903, she was overwhelmed by his celestial voice.

Gilles Laporte: “To write is to resist”

Did Ange exist?

No, he is a completely fictional character. He was born of two encounters: the discovery in the Vosges of a character with a historical role completely forgotten today, Joseph Pothier, who became Don Joseph Pothier. He was the great renovator of Gregorian chant at the end of the 19ᵉ century. And then I went to Normandy where I visited the abbeys of Saint-Wandrille and Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville. In the first, I discovered this Don Joseph Pothier, appointed by the Vatican to raise the abbey after its ruin by the Revolution. In the second, I saw an organ built by an organ builder, Guillaume Lesselier, so beautiful that I fell in love with it. I had found the subject of my next novel. A subject that puts a spotlight on our heritage, as (almost) always.

As in the other novels, I created a female character who wants to escape her condition as a woman as it was proposed at that time and become an organ builder.

She is a fictional character who is a link between Normandy, abbey and heritage, and the musical Vosges. She pulls out her Norman roots to replant them in the Vosges.

This book will be presented at the Livre sur la Place, in Nancy. How many books have you written? And how many times have you participated in the Livre sur la Place ?

I have written about sixty books, novels, essays and television scripts. And I have been present at all the editions of the Livre sur la Place since its origin in 1978. The very first one took place under the arcades of the Héré sidewalk. It was a terrible wind. We were about twenty authors and we did not see twenty visitors. I was surrounded by two remarkable writers whom I had always admired: Henri Vincenot, the Burgundian author, and Andrée Chédid. We stayed shoulder to shoulder for two days to keep each other warm. From there was born a very beautiful friendship between us.

Let’s talk about your production. Do you write every day?

Every day. Every morning from 4:30 – 5:00 to noon. I only write in the morning. I need the rising light. Perhaps there is a kind of atavism there because my parents were spinning mill workers, in the Vosges, and they took their job at the factory at 5 o’clock in the morning. I do like them, I take the job at the same time, but not on the same machine.

Before writing, do you do any investigative work?

Always. It’s almost like a journalistic investigation, which means traveling to the regions where I set down roots for my stories. I can’t talk about a region or a country if I haven’t been there.

What does writing mean to you?

It’s a militant act. This need to write dates back to elementary school. My first school teacher, Mrs. Jungen, invited me to share her love of language, especially through reading. I certainly fell in love with the teacher, as many students do, but mostly with the language. If for the teacher, it’s long gone, for the language, it’s still there. The defense and promotion of the French language is one of my driving forces.

My teacher was so successful that in first grade, I won the reading prize, I received the Don Quixote by Cervantes, illustrated edition for children. I always have it with me. It doesn’t leave me.

And then, all that matured and writing became for me an act of militancy, an act of resistance against those who want to kill our memory, our culture, our language and make sure that we are not ourselves anymore.

At the Livre sur la Place, you will meet your audience. What questions do they ask you?

It is a very curious and faithful public. They ask me about my books, why I write, why I write at such a pace (one or two books a year). They ask me questions about the political register, in the noble sense of the term. From my novels, they wonder about the current situation, the condition of women in our society, individual responsibility, civic behavior… Literature is for me a militant approach. I like to repeat to the pupils and students I often meet, to my readers: “Writing is Resistance!”