The 65ᵉ session of the Franco-Russian seminar co-organized by the Centre d’Études des Modes d’Industrialisation of the École de Guerre Économique (Paris) and the Institute of Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow) was held in Paris from July 3 to 5, 2023. Jacques Sapir, a well-known journalist and economist, gives an edifying account of the event, published on the “Les crises” website.

What kind of growth for 2023?

An important discussion is taking place regarding the Russian economy’s growth prospects for 2023. Some economists anticipate a sharp slowdown in growth in the course of the 2ᵉ half-year 2023, which should limit total growth to 1% or 1.5%. Note that these figures, which may appear disappointing compared with the data of recent months, are still well above the estimates that were made at the start of 2023 (January-February), which forecast a -0.7% recession for 2023. Growth of between 1% and 1.5% would be an improvement on the IMF forecast (April 2023) of +0.7% for 2023.

The arguments in favor of low growth in 2023 are as follows:

- Investment appears to have weakened markedly in Q1ᵉʳ 2023 and is expected to remain weak in Q2ᵉ.

- The “new equipment” content of investments in 2022 was lower than in 2021 (35.5% vs. 39.5%)

- The Central Bank’s fiscal policy and monetary policy could become more restrictive.

- Exports will no longer play the role of growth “locomotive” as they did in 2022.

- The fall in the exchange rate (intended by the Central Bank to maximize government tax revenues) will have a negative impact on household supplies and consumption.

This calls for several comments

There is currently a great deal of uncertainty surrounding the government’s economic policy. They have maintained the policy of supporting the economy and households to 1ᵉʳ quarter 2023, and accepted a relatively large budget deficit. The possibility of a “return to fiscal orthodoxy” is not to be underestimated. But, Russia is about to enter an election cycle (presidential elections in 2024). Logically, fiscal policy should remain relatively expansive, and the government is likely to maintain its “butter AND guns” policy, which has a clear effect on growth. Monetary policy poses another problem. Real interest rates are very high, due to the sharp fall in inflation. This could be a factor in slowing activity. However, bank credit plays little part in investment, and the multiplication of credit “bonus” mechanisms means that official rates are much less important than they were before 2022.

As for the exchange rate, it can be approached in different ways. Clearly, a depreciating ruble makes foreign purchases of equipment and spare parts more expensive, and tends to push up consumer prices, even if the proportion of consumer goods supplied by imports has fallen sharply. However, this depreciation increases the volume of taxes on imports, collected naturally in rubles, and enables a more expansive fiscal policy.

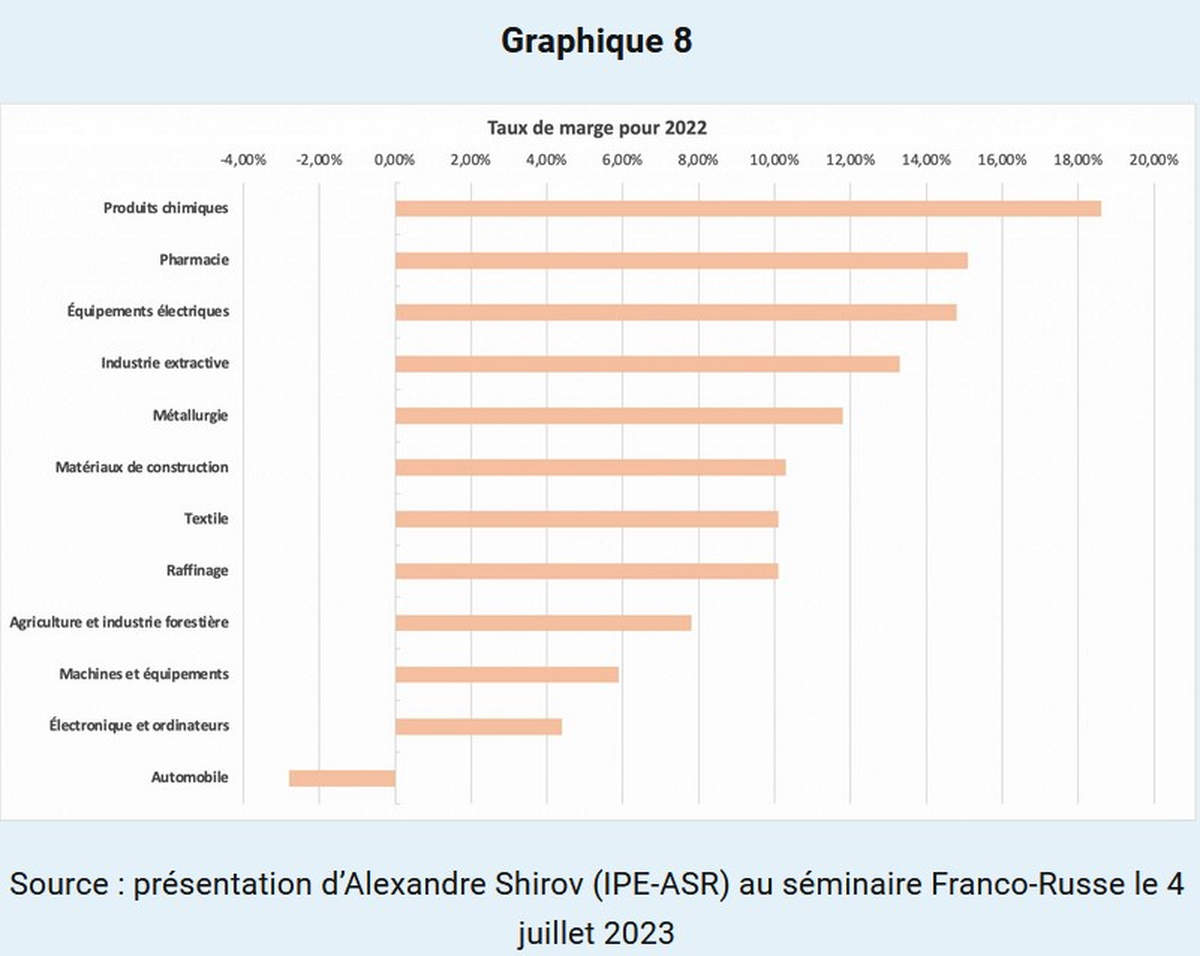

An analysis of the margin rate, which plays a decisive role in investment (both in terms of financial resources and future prospects), shows that it was particularly high in 2022, both for export-oriented branches (chemicals, metallurgy, mining) and for branches more focused on domestic consumption (pharmaceuticals, electrical equipment, building materials and textiles).

Those who take a more optimistic view are counting on growth of over 2% in 2022, with a maximum (potential growth) of 4%. The arguments in support of this view are as follows:

Private domestic demand is set to remain high, thanks to rising real wages and the revaluation of pensions and other benefits.

Public demand will remain high, both because of the continuing hostilities in Ukraine and the infrastructure programs launched by the government.

Businesses are moving towards strong growth, and their expectations are clearly optimistic.

These arguments have a certain relevance. Real wages should indeed continue to rise in 2023.

Table 4

Year-on-year changes in GDP, employment and apparent productivity

| PIB (glissement) | Emploi (glissement) | Productivité (glissement) | |

| 1ᵉʳ T 2022 | 103,0% | 101,0% | 102,0% |

| 2ᵉ T 2022 | 95,5% | 100,6% | 95,0% |

| 3ᵉ T 2022 | 96,5% | 100,0% | 96,4% |

| 4ᵉ T 2022 | 97,3% | 99,8% | 97,5% |

| 1ᵉʳ T 2023 | 98,2% | 101,9% | 96,4% |

| 2ᵉ T 2023* | 103,0% | 102,0% | 100,9% |

*estimates

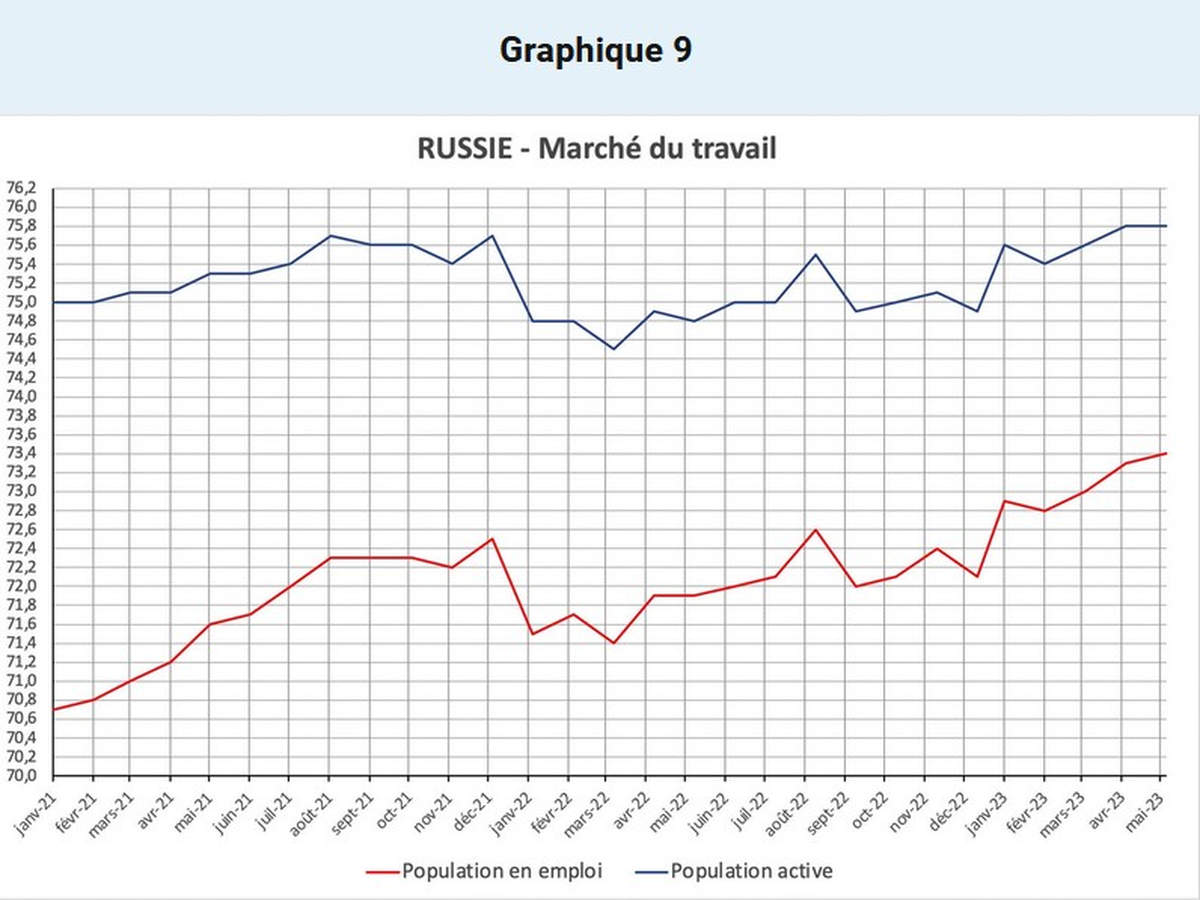

Indeed, there has been a significant rise in employment and a marked reduction in unemployment. This is leading to significant labor shortages in some regions. The decline in apparent labor productivity seen over the last four quarters (effect of sanctions and partial mobilization) is exacerbating the phenomenon.

In fact, the Russian economy can now be seen as more supply-driven than demand-driven. If we follow this line of reasoning, future growth can be better gauged by the pace of employment growth and the evolution of apparent labour productivity.

| ESTIMATED GROWTH based on employment and productivity assumptions | ||||

| H0 : Hypothèse de base | ||||

| Population employée | Accroissement | Accroissement de la productivité (glissement) | Accroissement du PIB | |

| Emploi 2021 | 71,717 | |||

| Emploi 2022 | 71,975 | 100,4% | 97,5% | 97,9% |

| Emploi 2023 | 73,500 | 102,1% | 100,5% | 102,6% |

| Emploi 2024 | 74,448 | 101,3% | 101,0% | 102,3% |

| H1 : rétablissement rapide de la productivité | ||||

| Population employée | Accroissement | Accroissement de la productivité (glissement) | Accroissement du PIB | |

| Emploi 2021 | 71,717 | |||

| Emploi 2022 | 71,975 | 100,4% | 97,5% | 97,9% |

| Emploi 2023 | 73,500 | 102,1% | 101,0% | 103,1% |

| Emploi 2024 | 74,448 | 101,3% | 102,0% | 103,3% |

| H2 : stagnation de la productivité et de l’emploi | ||||

| Population employée | Accroissement | Accroissement de la productivité (glissement) | Accroissement du PIB | |

| Emploi 2021 | 71,717 | |||

| Emploi 2022 | 71,975 | 100,4% | 97,5% | 97,9% |

| Emploi 2023 | 73,100 | 101,6% | 100,0% | 101,6% |

| Emploi 2024 | 73,800 | 100,5% | 100,0% | 100,5% |

The difference in estimates is +1.6%/+3.1% for 2023 and +0.5%/+3.3% for 2024. This shows the extent to which Russia’s growth will depend both on its ability to find manpower resources and to regain its pre-sanctions productivity levels.

One of the comments made by a proponent of a low growth rate for 2023 is that Russia will face a shortage of the machinery and equipment needed to speed up the modernization of its economy. In response, the rise in imports, which have now returned to their late 2021/early 2022 level, contradicts this hypothesis.

Furthermore, productivity growth depends not only on the material structure of equipment, but also on the rationalization of work organization and the flexibility of the relationship between companies and their subcontractors. It therefore seems reasonable to assume that productivity will gradually return to its pre-sanctions level. As for labor, it represents the biggest obstacle to maintaining high growth rates in the medium term. However, the constraint posed by Russian demographics in this respect can be lifted both by “internal immigration” (accelerating the fluidity of the labor market) and by external immigration. From this point of view, the current fall in inflation is probably not sustainable, either because of a possible “wage-price-wage” loop induced by the situation on the labor market, or because of the depreciation of the current exchange rate. It could resume at a relatively high level of 5% to 7% in the course of the 2ᵉ half-year 2023.

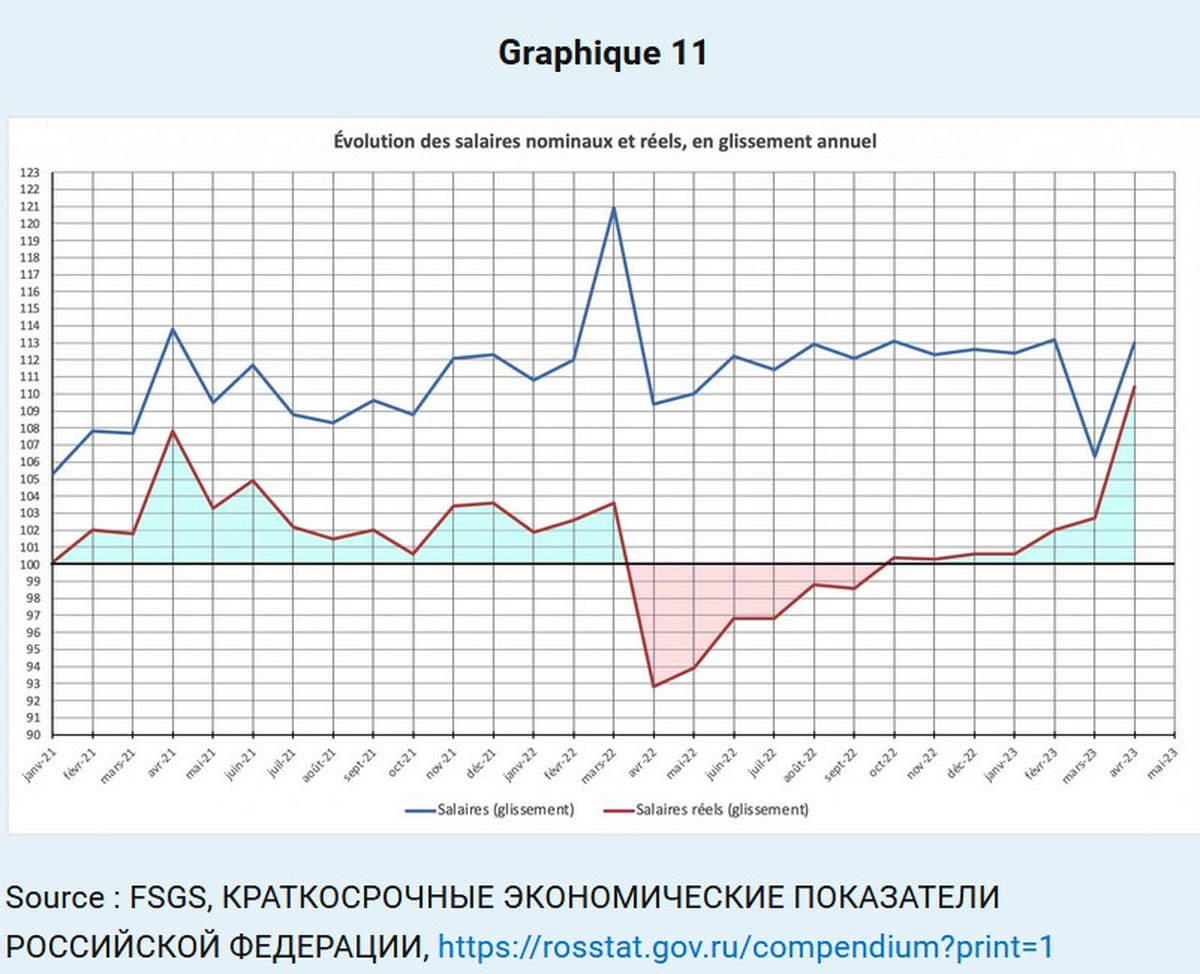

It should be noted, however, that real wages, after having fallen sharply as a result of the inflation peak in April-May 2022, began to rise again in October 2022, under the dual effect of rising nominal wages and falling inflation.

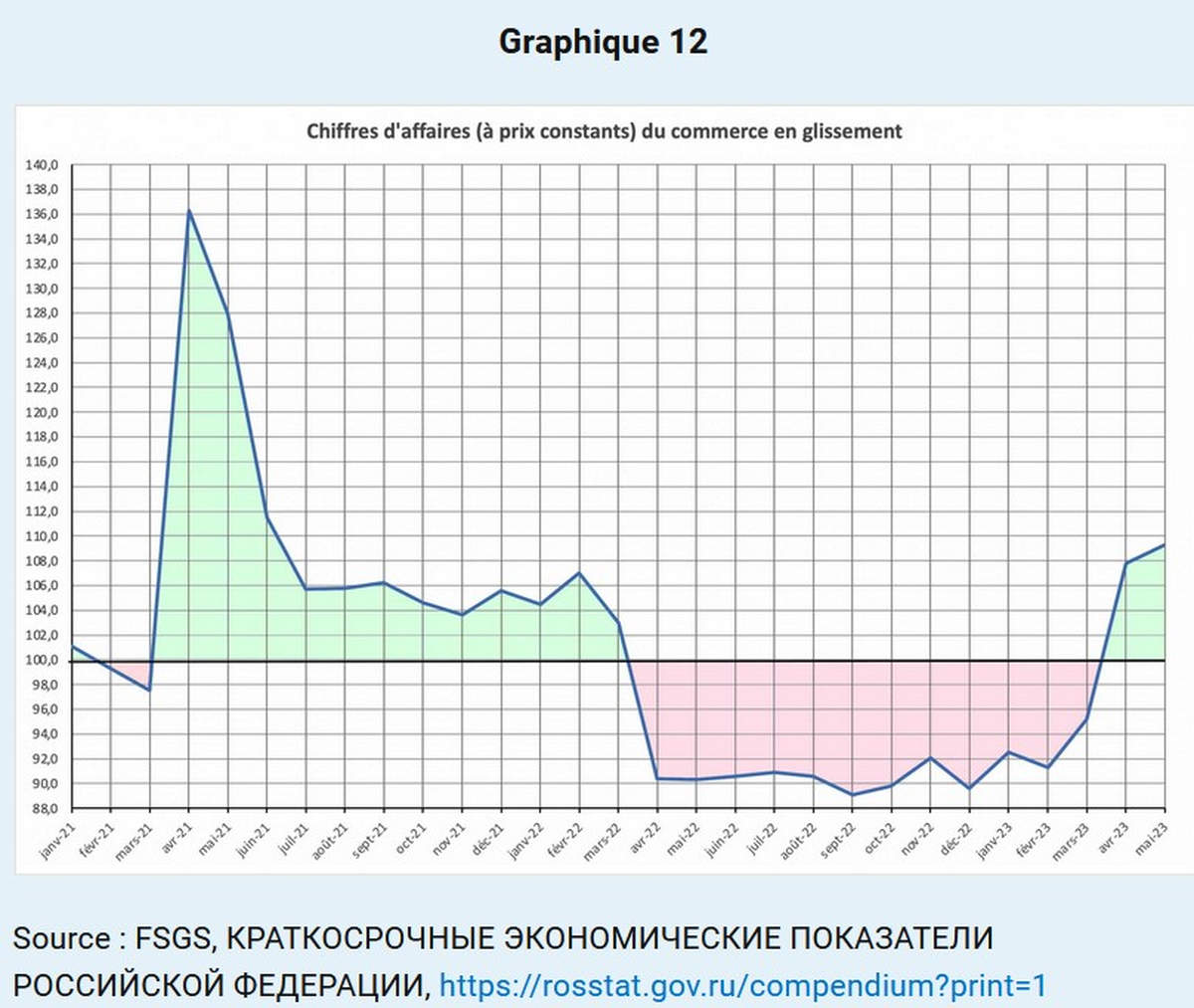

This rise has accelerated since February 2023, reaching over 10% in April 2023. The fall of 2ᵉ quarter 2022 is therefore on track to be offset, and even beyond. This translates into a sharp increase in retail sales.

This indicator of household consumption had fallen by more than the fall in real wages, due to the uncertainties arising from the hostilities in Ukraine. Households’ propensity to save had increased significantly. The sharp rise in April and May 2023 indicates that household consumption has returned to pre-crisis levels.

In any case, growth factors remain important at the end of the 1st half of 2023. This is borne out by the rise in revenues transiting through the Central Bank of Russia in Q2 2023, and particularly in June 2023 [5]. Economic growth should therefore be relatively high over the year, exceeding IMF forecasts (+0.7%) and certainly equal to or exceeding 1.5% in 2023. It should remain at a good level for 2024 if the government’s policy of support continues.

Medium-term outlook

Turning now to the medium-term potential of the Russian economy, several points have been made which merit attention.

Firstly, current geopolitical developments have profoundly altered Russia’s economic geography. Economic (as well as political, scientific and cultural) relations with the countries of the European Union are frozen. Whereas before 2022, Russia appeared as a “bridge” between the West and the East, for several years to come, Russia’s western border will be a “dead” border with very little traffic. Conversely, the importance of border areas with Asia (China, Korea, Japan) will increase rapidly. This could lead to a long-term shift. Cities such as Vladivostok, but also Khabarovsk and Komsomolsk-na-Amure, will take on new importance and will no longer be merely transit points for East-West flows, but rather Russia’s “outposts” in Asia. A public policy of infrastructure development in Eastern Siberia and the Far East will become essential relatively quickly. This is already the case for transport infrastructures (gas and oil pipelines, but also railroads). But these infrastructures cannot be limited to transport. To make it easier for companies to locate close to what will be Russia’s main market over the next twenty years, housing and support infrastructures will have to be developed.

Overall, geopolitical developments will also have major consequences for transport networks. From this point of view, the development of what the Russian authorities call the “North-South Corridor” – in other words, access from Russia to Iran and the Persian Gulf – will become a priority. In addition to providing Russia with a maritime outlet, it has the potential to speed up the transit of goods to countries such as India and Pakistan. However, the development of this corridor will have multiple consequences. Not only will it require the construction of major infrastructures, but this corridor will certainly be built with an “Eastern” and a “Western” branch in relation to the Caspian Sea. This will involve developing relations with countries such as Azerbaijan and Armenia, as well as Central Asian countries. The development of this corridor will also change the weight of certain regions in Russia itself, with cities such as Kazan, Astrakhan, Volgograd, Saratov, Samara and Ulyanovsk taking on new importance. Finally, it’s worth noting that this corridor will connect with China’s “Silk Road” projects, which run from East to West towards Turkey and the Balkans. It will be interesting to monitor the coherence of these two projects, which could come together in Iran.

These developments will also have an impact on Russia’s neighbors. Armenia, which has benefited greatly from the developments of 2022 (with the creation of over 1,100 companies by Russian capital) and which has experienced very strong growth (+12%), could consolidate its position as a platform for Russian companies if it manages to fit in well with the “Western” branch of the North-South corridor. Relations with Iran, already important, are set to grow.

nversely, Belarus faces a complicated situation. It is losing its role as a transit hub between the countries of the European Union and Russia. However, the level of development of its industries could enable it, in the context of closer integration with Russian industry, to benefit from investments in import substitution.

Finally, the geostrategic changes that have taken place since the end of February 2022 will also have consequences for the Russian financial system. While the Ruble/USD exchange rate currently remains the central exchange rate for the Russian economy, the rise in the volume of material and financial transactions in Yuan could make the Ruble/Yuan rate appear as a new pivot.

Moreover, the large budget deficit could enable Russia to develop its financial relations on the basis of a regional circulation of the Ruble, an old project that the Russian authorities have been nurturing for over ten years, but which, with the debt/GDP ratio rising to values in the 20% to 25% range, could take on a new reality in the coming years.

Conclusion

The Russian economy has adapted remarkably well to the new situation created by the “economic war” measures taken by Western countries. This adaptation characterizes both the macroeconomic and the microeconomic dimensions. This adaptation explains the mild recession Russia experienced in 2022, despite apocalyptic forecasts. This adaptation will enable relatively strong growth in 2023 and probably in 2024.

But this adaptation is not yet complete, and will require major restructuring of industry and agriculture. The need for modernization will remain high until apparent labor productivity returns to and exceeds its level at the end of 2021. The economy will therefore remain dependent on public aid and various support measures for another 18 months. The dynamics of the private sector do not seem capable of guaranteeing a satisfactory level of activity before 2025. The continuation or otherwise of public policy to support industry will be a determining factor in Russia’s economic dynamic for 2023 and 2024.

Jacques Sapir

Director of Studies at EHESS and lecturer at the Ecole de Guerre Économique

Director of CEMI-EGE

Foreign member of the Russian Academy of Sciences

List of participants

Boris Nikolaevich Porfiryev – Scientific Director of IPE-ASR, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Alexander A. Shirov – Director of the Institute of Economic Forecasting of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IPE-ASR), corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Dmitry Kuvalin – Deputy Director of IPE-ASR, Doctor of Economics, Head of Laboratory

Oleg Dzhondovich Govtvan – Chief Researcher, IPE-ASR, Doctor of Economics

Igor Eduardovich Frolov – Deputy Director, IPE-ASR, Doctor of Economics

Yury Alekseevich Shcherbanin – Head of Laboratory, Institute of Economics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Ph.

Valery Semikashev – Head of Laboratory, Institute of Economics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Candidate in Economics

Elena Valerievna Ordynskaya – Head of Laboratory, Institute of Economics, Russian Academy of Sciences, candidate in economics

Alexander Olegovich Baranov – Deputy Director of the Institute of Economics and Trade of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences (Novosibirsk), PhD in economics

Mariam Voskanyan – Head of the Department of Economics and Finance, Institute of Economics and Business, Russian-Armenian University, PhD in Economics, Professor

Ashot Tavadyan – Head of Department, Russian-Armenian University, Doctor of Economics, Professor

Irina Petrosyan – Head of Department, Russian-Armenian University, candidate in economics

Alexander Vladislavovich Gotovsky – Deputy Director of the Institute of Economics of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Belarus, candidate in economics

Jacques Sapir – Director of the Centre d’études des modes d’industrialisation (CEMI-EGE), Director of Studies at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS), lecturer at the École de Guerre Économique, foreign member of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Hélène Clément-Pitiot – Researcher at CEMI-EGE, Senior Lecturer at the University of Cergy-Pontoise and CEMI.

Jean-Michel Salmon – Lecturer at the University of Martinique (Université de la Martinique), CEMI-EGE researcher.

Renaud Bouchard – Researcher at CEMI-EGE

Maxime Izoulet – Researcher at CEMI-EGE, Éducation nationale.

David Cayla – Lecturer at the University of Angers (University of Angers)

Note

[5] BCR, Monitoring Otraclebykh Finansovykh Potokov, No 7 (76) / 06.07.2023

How has the Russian economy held up under sanctions since February 2022? (1/2)